| Tweet | Follow @co2science |

Paper Reviewed

Hurst, T.P., Copeman, L.A., Haines, S.A., Meredith, S.D., Daniels, K. and Hubbard, K.M. 2019. Elevated CO2 alters behavior, growth, and lipid composition of Pacific cod larvae. Marine Environmental Research 145: 52-65.

Writing in the scientific journal Marine Environmental Research, Hurst et al. (2019) correctly acknowledge that "the lack of a consistent response among larval fishes to elevated CO2 levels continues to challenge our ability to draw large-scale conclusions about the ecosystem impacts of ongoing ocean acidification." Indeed, and it is thus disingenuous for anyone to claim otherwise.

A good example of why one should not be so quick in jumping on the ocean acidification-is-certain-death bandwagon, as so many climate alarmists do, is presented in Hurst et al.'s paper, where, among other things, they examined the impacts of ocean acidification on Pacific cod (Gadus microcephalus). More specifically, their examined such impacts on newly hatched larvae from a captive adult cod broodstock that were reared under normal pCO2 conditions. Following spawning, newly-fertilized eggs were collected and incubated at ambient pCO2 levels (350 µatm) until hatching. Thereafter, yolk-sac larvae were transferred into one of two pCO2 treatment levels (502 or 1726 µatm, corresponding to seawater pH values of 7.98 and 7.43) where their growth and development were monitored two and five weeks later (corresponding to larvae developmental stages 6 and 9, respectively). In addition, half of the larvae in each pCO2 treatment were fed a nutritional-enriched diet (Diet 1) while the other half received a diet containing no nutritional enrichment (Diet 2).

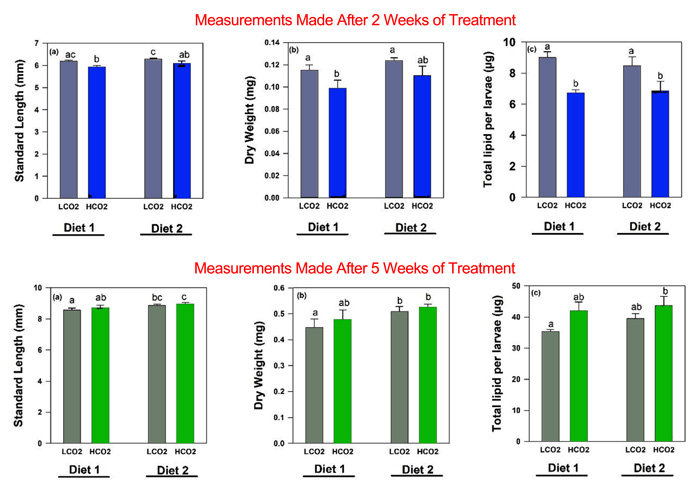

The results of the analysis revealed that fish in the high pCO2 treatment were "smaller and had lower lipid levels at 2 weeks of age than fish at low (ambient) pCO2 levels." However, Hurst et al. report that three weeks later "this effect had reversed: fish reared at elevated pCO2 levels were slightly (but not significantly) larger and had higher total lipid levels and storage lipids than fish reared at low pCO2." Similarly, fatty acid composition was significantly different between fish reared in the low and high pCO2 levels after two weeks, but this effect "diminished by week 5."

In light of the above, if Hurst et al.'s experiment had terminated after only two weeks of pCO2 enrichment, the logical interpretation of their data would have been that ocean acidification negatively impacts cod larvae. Yet, because their experiment persisted for three more weeks, the authors were above to offer this optimistic assessment, that "the sensitivity of Pacific cod larvae to elevated pCO2 varies with developmental stage," where "not only did older larvae not suffer the reduced growth and energy storage observed in the early stages, they actually exhibited the opposite response, an increase in growth rate."

Nevertheless, there remains yet a third possibility with respect to the future outlook of cod under ocean acidification conditions, which possibility is even more optimistic. As acknowledged by Hurst et al., it is quite possible that the perceived negative impacts of ocean acidification measured at week two of the treatment is an artifact of "acclimation to the effects of elevated pCO2." In fleshing out this thesis, the researchers note that "studies of the potential impacts of OA on marine fish larvae generally impose elevated pCO2 treatments around the time of fertilization or hatching (as done here). As a result, developmental stage is often functionally linked to the exposure duration, making it difficult to unambiguously discriminate ontogenetic effects from physiological acclimation."

It is quite possible, therefore that had the researchers conducted their experiment across multiple generations, with adult fish reared in a high pCO2 environment, and the ensuing fertilized eggs as well, there might have been no growth-related differences (or perhaps evidence of a growth benefit) observed in the two-week-old larvae. And until all ocean acidification experiments implement such protocol, it would be wise for climate alarmists to scale back their negative predictions on this topic.

Figure 1. Body length, dry weight and lipid levels of larval Pacific cod reared on two different diets at low (light bars, 557 µatm) and high (dark bars, 1760 µatm) pCO2 levels. Measurements were made at 2 (upper panel) and 5 (lower panel) weeks after the start of treatment. Source: adapted from Hurst et al. (2019).