| Tweet | Follow @co2science |

Paper Reviewed

Coles, S.L., Bahr, K.D., Rodgers, K.S., May, S.L., McGowan, A.E., Tsang, A., Bumgarner, J. and Han, J.H. 2018. Evidence of acclimatization or adaptation in Hawaiian corals to higher ocean temperatures. PeerJ 6: e5347, DOI: 10.7717/peerj.5347.

In a sobering and telling statement, Coles et al. (2018) write in the Abstract of their new paper that "predicted projections for the state of reefs do not take into account the rates of adaptation or acclimatization of corals as these have not as yet been fully documented." So perhaps it should come as no surprise that by not including this key aspect of life (i.e., the ability of living organisms to acclimate, acclimatize or adapt to changes in their environment), many have projected that future climate change will lead to the collapse of coral reefs within the next few decades (see, for example, the works of Hoegh-Guldberg, 1999; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007; Veron et al., 2009; Frieler et al., 2013).

But is this really the case? Are the so-called "rainforests of the sea" destined for disaster because of climate change?

Seeking answers to this question, Coles et al. set out to "assess possible changes in thermal tolerances" of three coral species (Lobactis scutaria, Montipora capitata and Pocillopora damicornis). Back in 1970, samples of these corals were collected from the Moku o Lo'e reef in Kane'ohe Bay, O'ahu, Hawaii, USA, and subjected to one month's duration of elevated temperature (31 °C), following which temperatures were returned to normal (26.4 °C). During the one-month period of elevated temperatures, and for one month after temperatures were returned to normal the authors conducted a series of measurements pertaining to the corals' growth and survival.

In 2017, nearly five decades later, the original experiment was repeated using present-day coral samples and "identical methodology, location, seawater system, and observer." And finding that the baseline ambient sea surface temperature had risen 2.2°C since 1970, the current experiment provided the researchers with an opportunity to assess the corals' ability to acclimate or adapt to the warming trend.

And what did that experiment reveal?

The results indicated there were "significant differences in coral bleaching, calcification, survivorship, and mortality" between the two experiments. With respect to bleaching, Coles et al. note that it was observed "much sooner in 1970 compared to 2017 at similar temperatures," adding that "in 1970, onset of bleaching occurred in half the number of days (3 d) than in 2017 (6 d) in P. damicornis and M. capitata and three days sooner in L. scutaria (5 d vs. 8 d, respectively)."

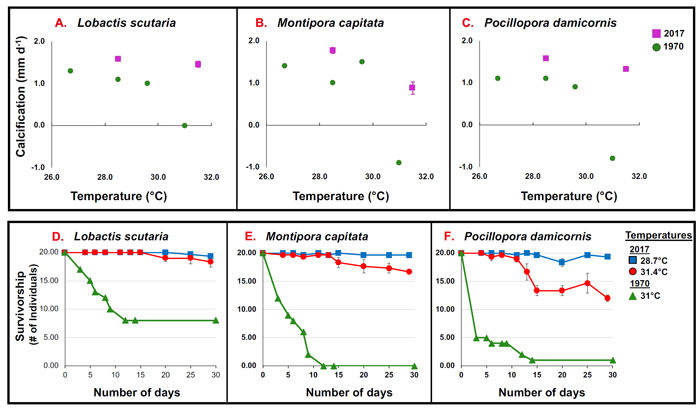

Calcification rates were reduced by high temperatures in both the 1970 and 2017 experiments, but the authors report that "reductions in 2017 were not as severe as those documented in 1970." In fact, comparison of calcification rates between the two periods revealed that they "were 70-90% higher in 2017" (see Figure 1, Panel A-C).

With regard to survivorship and mortality, Coles et al. report that "coral survivorship at elevated temperature (~31.4 °C) was higher in 2017 across species: L. scutaria (92%), M. capitata (83%), and P. damicornis (60%)." In contrast, in 1970, survivorship of L. scutaria was only 40%, P. damicornis 5% and M.capitata 0% (see Figure 1, Panels D-F).

In light of the above findings, Coles et al. state the obvious, that the corals "were able to withstand elevated temperatures (31.4 °C) for a longer period of time in the current 2017 experiment" compared to the 1970 study. Consequently, they conclude that their results "indicate a shift in the temperature threshold tolerance of these corals to a 31-day exposure to 31.4 °C," which findings "provide the first evidence of coral acclimatization or adaptation to increasing ocean temperatures." And that observational reality should hold great bearing on the status and health of coral reefs in response to future climate change. If temperatures rise in the future, clearly, as living organisms, corals can (and do!) adapt. Alarmist predictions of their fast and ensuing demise due to global warming should not be taken too seriously.

Figure 1. Panel A-C: calcification of tested coral species during 1970 (green circles) and 2017 (violet squares) across experimental temperatures. Panel D-F: Survivorship (number of individuals; > 95% partial mortality) of the tested coral species at 2017 summer ambient temperatures (28.7 °C; blue squares), and current heated treatments (31.4 °C; red circles) and in 1970 (31 °C; green triangles). No mortality was observed in 1970 summer ambient treatment (26.4 °C). Source: Coles et al. (2018).

References

Frieler, K., Meinshausen, M., Golly, A., Mengel, M., Lebek, K., Donner, S.D. and Hoegh-Guldberg, O. 2013. Limiting global warming to 2°C is unlikely to save most coral reefs. Nature Climate Change 3: 165-170.

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. 1999. Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world's coral reefs. Marine and Freshwater Research 50: 839-866.

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Mumby, P.J., Hooten, A.J., Steneck, R.S., Greenfield, P., Gomez, E., Harvell, C.D., Sale, P.F., Edwards, A.J., Caldeira, K., Knowlton, N., Eakin, C.M., Iglesias-Prieto, R., Muthiga, N., Bradbury, R.H., Dubi, A. and Hatziods, M.E. 2007. Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science 318: 1737-1742.

Posted 12 November 2018