| Follow @co2science |

Paper Reviewed

Wang, L., Hu, M., Zeng, W., Zhang, Y., Rutherford, S., Lin, H., Xiao, J., Yin, P., Liu, J., Chu, C., Tong, S., Ma, W. and Zhou, M. 2016. The impact of cold spells on mortality and effect modification by cold spell characteristics. Scientific Reports 6: 38380, DOI: 10.1038/srep38380.

In the debate over CO2-induced global warming, studies investigating the impact of heat waves on mortality far outnumber those that examine the impact of cold spells. Indeed, according to Wang et al. (2016), such is the case in China, where "the health impact of cold weather has received little attention, and only a few studies have examined the health effects of cold spells and these were mostly focused on a single or few cities."

Hoping to remedy this situation and provide a clearer picture of the subject, Wang et al. collected daily mortality and meteorological data from 66 communities across China over the period 2006-2011. They then subjected these data to a series of analyses to elucidate the relationship between cold spell characteristics and human mortality. And what did those analyses reveal?

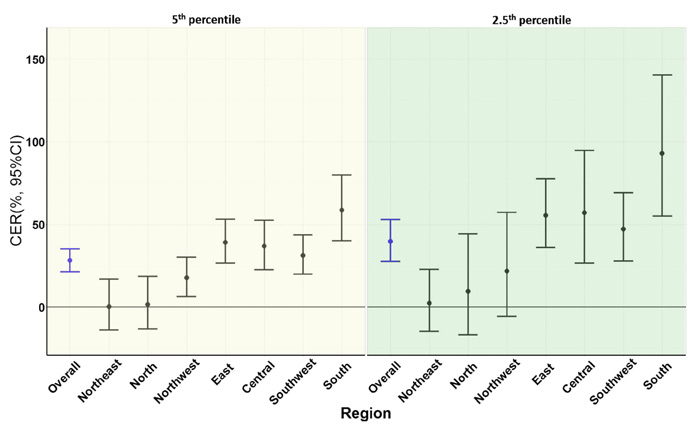

Not surprisingly, cold spells significantly increased human mortality risk in China. As indicated in Figure 1 below, the combined cumulative excess mortality risk (CER) for all of China when defining cold spells with a 5th and 2.5th percentile temperature intensity threshold was 28.5 and 39.7 percent, respectively. However, there were notable geographic differences; CER was tempered and near zero in the colder/higher latitudes, but increased to 58.7 and 92.9 percent at the corresponding 5th and 2.5th percentile temperature intensity thresholds for the warmest and most southern latitude. Such geographic differences in mortality risk, according to the authors, is likely the product of better physiological and behavioral acclimatization of the northerly populations to cold weather.

Figure 1. Summary cumulative excess risk (CER) of different intensity of cold spells on total non-accidental mortality during lag 0-27 days in different regions of China, 2006-2011. In the left panel (yellow shading), a cold spell was defined as a weather fluctuation if the mean daily temperature fell below the 5th percentile of the study period in a specific community for at least 2 consecutive days. In the right panel (green shading), a cold spell was defined as a weather fluctuation if the mean daily temperature fell below the 2.5th percentile of the study period in a specific community for at least 2 consecutive days. Source: Wang et al. (2016).

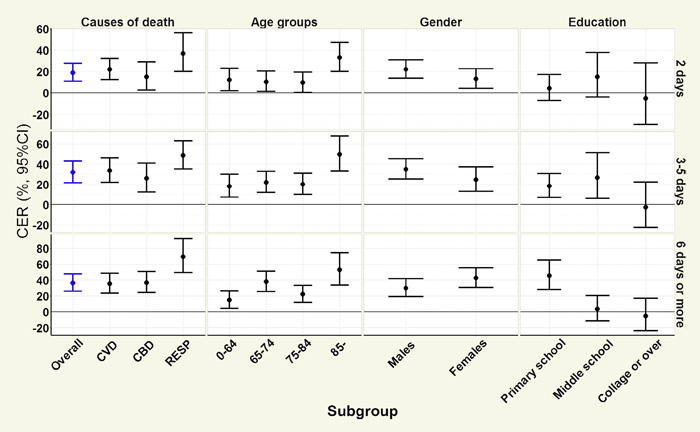

Wang et al. also report that the strength of the temperature/mortality relationship was modified by cold spell characteristics and human-specific factors, such that there was a significant increase in non-accident mortality during cold spells that were longer, stronger and/or earlier in the season. In addition, mortality rates were found to increase by age and decrease by education level; the older and less educated tended to experience the greatest risk of death (see Figure 2). The health status of an individual was also a factor. Those with respiratory (RESP) illnesses had higher CER rates than those suffering from cardiovascular (CVD) or cerebrovascular (CBD) diseases (see Figure 2).

Clearly, cold spells kill; and as has been found in almost every study of the subject, the risk of death from cold spells far exceeds that from heat waves (see the many reviews we have posted on this topic confirming this fact in our Subject Index under the heading Health Effects of Temperature: Hot vs, Cold Weather). As such, therefore, a little global warming would likely result in a net saving of lives by reducing the number of deaths that occur at the cold end of the temperature spectrum.

Figure 2. Summary cumulative excess risk (CER) of cold spells with different duration on total non-accidental mortality during lag 0-27 days in China, by age, gender, education, and causes of death. Source: Wang et al. (2016).