| Follow @co2science |

Paper Reviewed

Zhao, Q., Zhang, Y., Zhang, W., Li, S., Chen, G., Wu, Y., Qui, C., Ying, K., Tang, H., Huang, J., Williams, G., Huxley, R. and Guo, Y. 2017. Ambient temperature and emergency department visits: Time-series analysis in 12 Chinese cities. Environmental Pollution 224: 310-316.

The impact of global warming on temperature-induced human mortality has long been a concern, where it has been postulated that rising temperatures will lead to an increase in the number of deaths at the hot end of the temperature spectrum due to an increase in the frequency and intensity of heat waves. However, others have charged that rising temperatures will also reduce the number of deaths at the cold end of the temperature spectrum (fewer and less severe cold spells), resulting in possibly no net change or even fewer total temperature-related deaths in the future. The prevailing viewpoint to date is the latter, i.e., that global warming will be net beneficial to human mortality by reducing the total number of lives lost to temperature-related events (i.e., heat and cold waves). This fact is evident in the many articles we have reviewed on this topic and posted on our website under the heading Health Effects (Temperature: Hot vs. Cold Weather).

The latest work adding to this ever-growing body of evidence comes from Zhao et al. (2017). As their contribution to the subject they examined the association between daily mean ambient temperature and emergency department visits (an analog of mortality) in twelve Chinese cities over the period 2011-2014. The twelve cities represented two in the north, six from the central region and four in the south, covering a wide range of latitudes and temperature regimes. A quasi-Poisson regression with distributed lag non-linear model was utilized to examine each city's relationship between daily mean temperature and emergency department visits, the result of which were then pooled to yield regional and national findings.

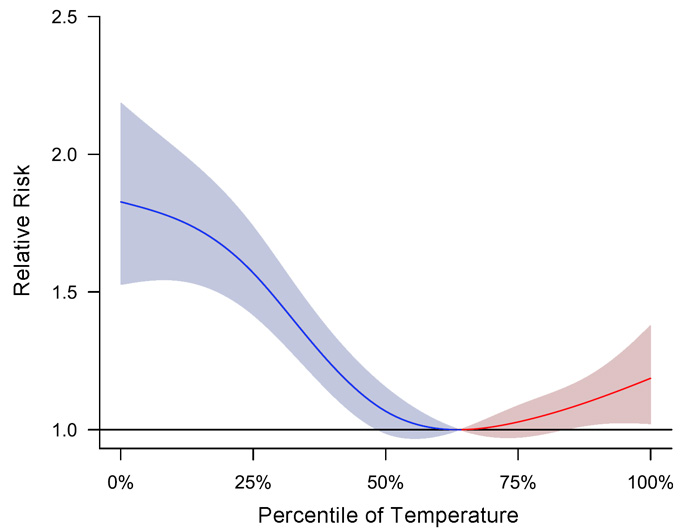

As represented by the pooled national data as shown in the figure below, the results indicated that the relative risk of emergency department visits increases as temperatures become both warm and cold. However, the risk is far more severe with cold temperatures, where the cumulative relative risk was 1.80 versus a much smaller 1.15 that was associated with hot temperatures. Additionally, Zhao et al. determined that the effects of cold spells on emergency department visits were much more persistent, lasting a full 30 days compared to the more acute, but short lived, effects of warm spells that lasted a mere 3 days, or one-tenth of the time.

Figure 1. Pooled national level cumulative association between temperature and emergency department visits over a lag of 0-32 days during 2011-2014. Natural cubic spline with 4 and 5 degree of freedom was used for temperature and lag days, respectively. Adapted from Zhao et al. (2017).

Other important findings included the observation that the temperature percentile associated with the least amount of emergency department visits was 64. At 14 percentage points higher than 50, this fact suggests that the population is much more adapted to warmer temperatures than cold. Zhao et al. also found that the temperature effect on emergency department visits varied by latitude; the effect of extreme cold was higher in the southern cities and declined northward, whereas the effect of extreme heat was higher in the northern cities and declined southward, which findings suggest a form of regional adaptation to temperature.

In stratifying their analysis by gender and age, the thirteen researchers report the temperature/emergency department visit relationship was unaffected by gender but was attenuated with increasing age. At the national level, the relative risk of emergency department visits due to cold declined from 2.27 for the youngest age group (0-14 years) to 2.17 for ages 15-34, 1.60 for ages 35-64 and 1.41 for the elderly aged 65 and older. Similarly, the risk of emergency department visits due to hot temperatures also declined from 1.51 for 0-14 years to 1.19 from ages 15-34, 1.14 for ages 35-64 and 1.08 for those over age 65. Thus, children ages 0-14 were considered to be the age group of the population that was most vulnerable to cold spells and heat waves over the period of study.

In considering all of the above findings, plus those reported in numerous other studies of the subject, it is clear that the impact of cold weather on human health is much more severe and longer lasting than that caused by heat waves. The truth be told, humanity has much more to gain in terms of physical heath from rising, as opposed to falling, temperatures.

Posted 28 July 2017